|

|

|

|

|

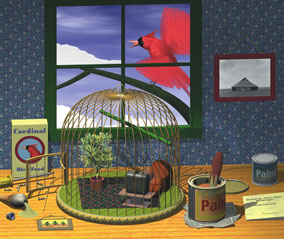

| Birdcage: I like

telling stories and find it easier to do in 3-D than with photography.

This is a story of someone who wants to entice a cardinal to be his pet.

Modeled and rendered in form Z. |

From photographing in Long Beach, New

York, as a child with his father, Peter Neumann progressed to shooting

and printing his own large-format black-and-white landscapes. Next came a

career as a commercial studio still-life photographer. When this work

began migrating to digital, Neumann waded into Photoshop and produced

corporate projects with it until discovering his true medium, 3-D

digital illustration. His work has appeared in Forbes, Art Business

News, Upside Magazine, CFO Europe, the American Management Association,

Graphic Arts Monthly, Executive Edge, Corporate Finance, Global

Investment Magazine, and annual report projects for the Federal Reserve

of New York and the American Federation of Teachers. In addition, Photo

Trade News, Micro Publishing News, Photo Electronic Imaging, Digital

Imaging, and Japan's i Magazine have featured his 3D. His landscape

images have been exhibited in several U.S. galleries and are included in

the collections of the Brooklyn Museum of Art, Pfizer, Bloomingdale's

and several private collections. His 3-D image Absolute Hangover was in

the Brooklyn Museum's 27th exhibition in its Print National series,

"Digital: Printmaking Now."

I asked Peter about these

transitions at his studio in the heart of New York's Photo District. As

he pointed out, it's now also the home of Silicon Alley, full of

dot-coms and other digital enterprises. While he creates illustrations

in his digital studio, he rents his photo studio across the hall and

rents out his darkroom when not using it himself for his personal fine

art black and white landscape work-because the focus is clear: 3-D has

taken over his creative life.

Photo Insider (PI): When did you start photographing?

|

|

| Gas Pump: The Pump,

lamp and road were originally done for Convenience Store News Magazine. I

wanted to add something to the image and saw the perfect building at a

Walker Evans exhibit Evans's love of old signs also inspired this image.

Modeled in form Z and rendered in Electric Image. |

Peter Neumann (PN): As a child

in the 1950s, my father and I would take bicycle rides around my

hometown of Long Beach. We'd carry a Plaubel Makina, 6x9, folding camera

with archaic film packs and take pictures of each other. We shot with

an 8mm movie camera, too. My father also traveled a lot to Europe on

business and would show slides when he returned. He was a glove designer

(the actress Joan Crawford used to wear his gloves) and an excellent

oil painter. Photography was always a part of our family.

PI: What did you study?

PN: My path to photography

wasn't a straight line. I majored in literature at Northeastern

University in Boston and spent years learning to play guitar and compose

music, which I still do.

PI: When did the idea of professional photography enter the picture?

PN: In 1979-80, after a

brief foray into photojournalism, I bought a 4x5 Deardorff view camera

and began shooting landscapes. At the time, I was earning my living at a

clerical job at the United Nations.

In the summer of 1980, I

took a long vacation camping out west with the 4x5, shooting landscapes

in black and white. It was an amazing thing to travel across the country

looking for beauty.

|

|

| Homage to Irving Penn: This is a 3-D version of his still life After-Dinner Games. Modeled and rendered in form Z. |

PI: How did you learn large-format technique?

PN: On my own. I read

everything I could, and I shot a lot. In Jackson Hole, Wyoming, I went

to a gallery where I met a photographer, Ed Riddell, who was shooting

landscapes and still life and interiors. I thought, "This is incredible.

You can do this as a living." That's how naive I was. I kind of took

photography for granted. I saw it as just being part of life...thanks to

Kodak and my father, I guess! When I came back to New York, I stayed on

in my job and took another long photography trip the following year.

After that, I quit to pursue photography full time. At first, I shared a

studio with another photographer.

PI: What type of work were you doing?

PN: Still-life, tabletop

shots of products like handbags and clothing. These demanded the most

minute attention to detail and contrasted dramatically with the

monumental scenery I loved photographing out west.

PI: How did you learn studio lighting?

PN: The person I shared the

space with, Stephan Tur, was very helpful and showed me a lot about

studio technique. But it was a slow learning process. Eventually, I

started getting better. I took over the studio myself, buying him out in

1984. I continued to do my personal landscape work and was exhibited in

various galleries.

PI: How did you get the commercial clients?

PN: I had been a marathon

runner and I applied that mentality to marketing, logging as many visits

and portfolio drop-offs as I possibly could. I talked to other

photographers, I used the phone book, and ad agency listings from

reference books at the library, like the advertising agency Red Book. A

lot of research went into developing a database of clients.

PI: How did you move to the next step?

PN: It started when I wanted

to put an ad in the Workbook. A rep came here and looked at my work and

said, "I think you should wait until your still life starts to look

like your landscapes." After my initial shock, I decided, "No more

products, I'm just going to shoot what I want to.

|

|

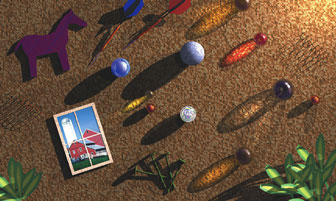

| Marbles in 3-D: I

wanted to see if I could get the feel of my marbles photograph using 3-D

software modeled in form Z and rendered in Bryce. |

"I was trying to find a style

because I knew that, ultimately, it would get me more work. I began

doing still-life compositions with handmade paper backgrounds and

objects that I found. My images became more imaginative and

off-the-wall, much more interesting. At this time, conventional

photography business was starting to drop off because of the digital

revolution. But I wasn't paying much attention due to illness in the

family. By about 1993, though, I decided that it was time to make some

changes. So I took some classes in Photoshop at the School of Visual

Arts in New York City. I didn't even know what a mouse was then, but I

really got turned on by Photoshop. A photographer friend, David Chalk,

was doing really beautiful work in 3-D and was a tremendous inspiration

to me.

PI: By "3-D" you mean three-dimensional digital illustration?

PN: In Photoshop, I didn't

feel that I could create certain effects and make the results look real.

I wanted to work in an ideal environment where the shadows were

natural, and that's what 3-D is. With 3-D software programs, you make a

shape, like a sphere, and you give it attributes such as bumpy or shiny,

and choose a color. Then you put that object on another surface which

has another texture. When you put a light on that object in a 3-D

program, it's going to cast a shadow that looks totally real.

One day, working with an

early 3-D program called Alias Sketch, I discovered that I could turn

off the harsh, straight-on default light source. Exactly as in a real

photo studio, I found that I could add lights in different positions. I

just about jumped out of my chair and said to myself, "This is like

still life. I know this."

|

|

| Marbles I shot with an 8 x 10 view camera using chrome film and lit with strobes. |

PI: Which 3-D programs do you use today?

PN: From Sketch I moved to

Strata Studio Pro and Bryce. I now use form·Z, which is a really good

modeler. A modeler builds shapes. Form·Z is great for architecture and

shapes that are geometric rather than organic, although that's changing

fast. It's often used in conjunction with another program, Electric

Image, which has a very fast rendering engine. Rendering is when you ask

the program to take the shape, texture, and light information and apply

it, pixel by pixel, to create the final image that looks like a

photograph or a picture. I am now learning Lightwave, too.

Back in the early days, I

was doing a relatively small illustration for a magazine, 4 by 5 inches.

I decided that I would let it render overnight. When I came in at 11

after a run the next morning, the rendering was only 59 percent done. In

order to make my deadline, I switched to Electric Image. With this

program it took all of 15 minutes to render the entire image! I was

converted. Now, I do my modeling in form·Z and then either render the

image in Form Z's RenderZone or export the file to Electric Image,

Bryce, or Lightwave where I apply surfaces, textures, and lighting

effects. Electric Image is used a lot in movies like Star Wars. It is a

gorgeous renderer. The colors look beautiful.

PI: How do you describe what you do?

PN: I call myself a

conceptual 3-D digital illustrator. At one point, I had a moment of

conversion when a client I had been doing conventional photography for

agreed to let me do an illustration. She asked me to illustrate a

concept. Thinking about how I was going to show this idea, coming up

with sketches late at night in bed-I had never had an experience like

that in photography. Clients always came to me with layouts, with

preconceived ideas. I did beautifully lit photography with great art

directors, but they did the concepts. And they selected, or oversaw the

building of, props. I just executed the photograph.

PI: Now you're creating the idea.

PN: That's what I started

doing with my still life before I weaned myself from the photography

world. It's taken me years to learn the technique of 3-D, but I feel

more and more fluid every day. My lighting's getting better, and I can

create props on-screen that would cost a fortune to have a model builder

make. One's attention to detail, and the magic of seeing the real

world, is taken to another level after learning how to work in 3-D. You

look at things differently.

PI: When you made the transition to digital, how did your marketing change?

PN: First, I bought a studio

management program called PhotoByte and transferred all my client

information into its database. I got hooked on the idea of illustrating

magazine articles. I love doing it because of the great freedom.

Granted, it doesn't pay as much as some photography. I go to newsstands

and bookstores, foraging for new publications that I'd like to work for.

Then I go home and call the art directors. Some years ago, I'd mail my

portfolio as a slide show on a floppy disk. But I'd never send something

unsolicited-I'd call somebody up and get them to say they were

interested. Then I'd mail it and call to be sure that they got it and

that the disk worked. Often the disk would be ruined in the mail.

|

|

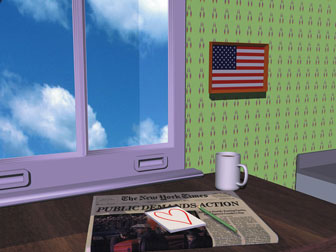

| September 2001:

September 11 left me pretty speechless. This image sums up how I felt

at the time. I also used this illustration as an opportunity to get

better at using Lightwave. Modeled in form Z and rendered in Lightwave. |

PI: So what do you do today?

PN: Because of the high

casualty rate for disks and because the new Macs don't have floppy

drives, I moved to the Internet. Marketing is about presenting your work

in a way that is quick and easy. About four years ago, I did a Web

site, www.peterneumann.com, which showcases my work.

PI: Did you create it yourself?

PN: I did it myself for two

reasons. It was cheaper, but primarily I felt I had to have the

experience and familiarity with what was happening on the Internet.

PI: How do you get people to see your site?

PN: I telephoned everyone in my database and got their e-mail address. Now I send them images periodically via the Internet.

PI: What equipment do you use and why?

PN: I use the Mac because

that's what I learned on and it's the platform a lot of digital

illustrators use. I use both a mouse and a Wacom tablet.

PI: Do you use digital cameras at all?

PN: No. Generally, I don't use photos except as reference to draw from, or for image maps to be placed on 3-D objects.

PI: For a digital illustration assignment, could you please describe all the steps from initial contact to delivery?

PN: Either I get the job via

e-mail or by telephone. The client has an article or an idea that they

want me to turn into a visual. They fax me the article, I read it and

come up with some ideas. For instance, I was recently asked to do an

illustration of binoculars with a computer reflected in the lenses with a

strong perspective. I look for related pictures, like old and new

styles of binoculars, on the Internet for reference, for ideas, and for

accuracy. Also, I use my own visual reference books.

Then I come up with two or

three different versions and make preliminary images, called roughs, in

form·Z and render them at a low resolution: 72 dpi (dots per inch).

After saving each image as a JPEG, I compress it with StuffIt and send

it to the client via e-mail. You can also insert a .jpg image in the

body of an e-mail letter without compressing it. After reviewing my

preliminary images (and we may do this a few times), the art director

tells me which version he or she prefers. Then I go back to my roughs,

render the selected one in high resolution, and e-mail it to the client,

along with an invoice.

To view more of Peter Neumann's work, visit his website.

|

|

|

|

|